Catching Up with Deke Sonnichsen

News

Posted by: International Skydiving Museum & Hall of Fame

5 years ago

By: International Skydiving Museum & Hall of Fame Staff

When Deke found out he was being inducted into the International Skydiving Hall of Fame, he had been involved in parachuting since his very first jump in 1951. Deke’s first five jumps happened in September of that year, all at the Army Parachute School at Fort Benning, Georgia, when the Korean War was in full swing.

“The gentleman who introduced me to — well, it wasn’t called ‘skydiving,’ just ‘parachuting’ — was a Master Sergeant named John Sweatish,” Deke says. “He was a World War II vet from Montana; an 82nd Airborne member. He was loaned by the 82nd to the OSS to drop agents into various places like Romania, Montenegro, Serbia and so forth. He asked me what I thought about jump school. I said it was okay. John asked me if I wanted to join an organization for just parachutists. I said sure, and so he gave me an application to the NPJR: National Parachute Jumpers and Riggers. I joined in early 1952, and that was it.”

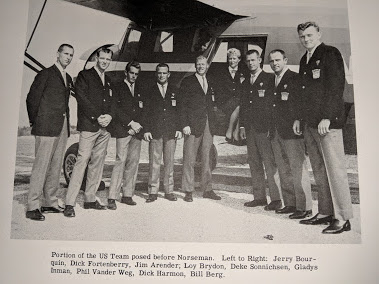

From that quiet beginning sprung story after story. Deke’s path in the sport led him from international competition to international competition. Deke strode confidently over to compete in the very first, much-ballyhooed Adriatic Cup (in what is now Montenegro) in 1957. He was also the Team Leader of the US Team in the 6th FAI WSPC (at Orange, Mass) in 1962. At that meet, Jim Arender (USA) and Miriel Simbro (USA) won the Worlds Championships:

Individual, Mens and Womens, respectively. He competed again at the 4th Adriatic Cup (in what is now Slovenia), and then again in deepest Bavaria for the 7th FAI WSPC. Deke has plenty of fun stories from those years when he was a very young, very tall, square-jawed military gent at the pointy end of the most exciting sport in the world.

“On my third visit to Yugoslavia in 1963,” he muses, “During Adriatic Cup number four — one of the events organized by the FAI in its early days — we were going for the first world championships, which were held in Bled, Slovenia. One of the events they organized was called the ‘crowd-pleasing event.’ For that, the teams could do whatever they wanted to try to do just that: try to please the crowd. By show of applause, the crowd awarded first, second and third.”

“Talk about low openings!,” he continues, laughing. “There were a lot of low openings. We had smoke on all of our jumpers, and that smoke got close enough to make you sneeze. The first two guys did a double diamond and opened at around 300 feet. That’s a little low, I’d say. And then Dick Fortenberry did a bunch of maneuvers in the air and then came down and landed in the crowd. He didn’t hit anybody, thank goodness — and he won a beautiful wooden statue of a parachutist, carved by a local.”

For all Deke’s team leadership and high-flying competition career, arguably, his most major contributions were right here on American soil. He’s held several offices in different versions of the USPA as it grew from infancy. A film produced by the California Parachute Club (“Sport of the Space Age”) won the Palm d’Or in the Sport Aviation category of the FAI World Aviation Film Competition, in 1964. Finally, he co-designed (and made plenty of test jumps on) one of the very first back-mounted reserve parachute systems, as well as key contributions to the Paracommander.

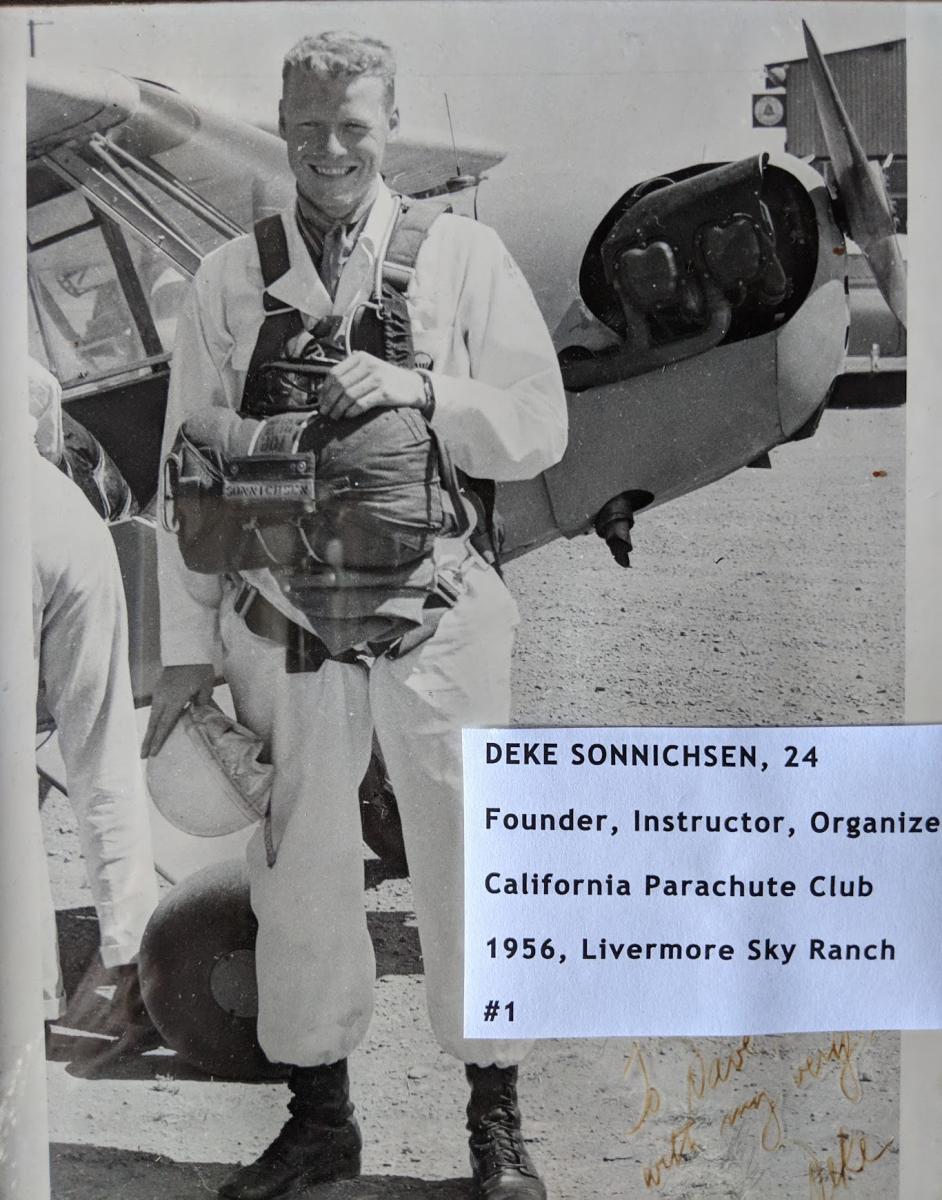

If you ask Deke what he’s most proud of, though, he’ll go into a different story. It’s about what happened in 1956 when he was just 24 years old. That year, he became the founder, organizer and chief instructor of the California Parachute Club, at their very own dropzone. Very notably beyond even that, the ribbon-cutting at the Livermore Sky Ranch represented the formation of the first sport parachute club in the USA.

At that point, what is now the USPA was still the NPJR, thought it was just about to change its name to the Parachute Club of America. There was no collective organizational mechanism in the NPJR: No mention of teams; no constitution; no bylaws; nothing. Having just come out of the Army (“which was certainly a team-oriented activity,” he jokes), Deke set about forming a team. Once that was a done deal, he began to push for that first club — the California Parachute Club — and led the club-forming effort all throughout the country and elsewhere in the world.

Other countries were certainly leaning in the direction of that zeitgeist. At the moment Deke started campaigning, the French had a dozen parachute schools — but all 12 of them were explicitly military, sited on military bases around France and run by the government. “Of course, the sport activity in the USA was all private,” Deke adds, “and had nothing to do with any government bodies, the FAA, or anything else of that nature.”

Newly-civilian Deke started to look around his Northern California stomping grounds. He dreamed of a place that he and his other sport jumpers could call home — not just a roaming club, but a dropzone just for them and the visiting jumpers he envisioned coming through. He heard about a sod strip near Livermore. During WWII, it had been the takeoff and crash base for an advanced-training Naval pilot school. When Deke moved in, he gave the first sport skydiving club a home — and therefore made a giant leap for skydiver kind. Deke still lives not far from there: In Menlo Park, which is just 30 miles south of San Francisco, between San Francisco and San Jose.

The Livermore Sky Ranch became part of the Livermore Muni Airport, but the love of skydiving still pumps through Deke’s adventuring veins. Even today, Deke has great advice for the sport skydivers who have followed in his footsteps.

“Always pull and open high. Don’t try to get close,” he advises. “The ground is uncompromising.”

Categories:

You May Be Interested In:

2025 Path & Pioneers of Excellence Recipients Revealed!

3 weeks ago by Nancy Kemble Wilhelm

Congratulations to Museum Trustee Sherry Butcher!

1 month ago by Nancy Kemble Wilhelm

Don Kirlin Joins Board of Trustees

3 months ago by Nancy Kemble Wilhelm

Congratulations Hall of Fame Class of 2025!

4 months ago by International Skydiving Museum & Hall of Fame

Join the Mission

Be Part of Skydiving History

As a nonprofit organization, we are counting on investments of time, talent, and resources from our collective community to make the International Skydiving Museum & Hall of Fame a reality.